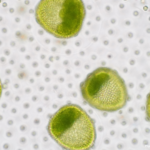

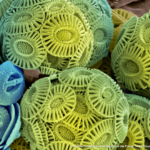

Phosphorus credits are tradable certificates representing a verified reduction of phosphorus pollution. Excess phosphorus – from fertilizers, manure, or sewage – causes algae blooms, oxygen-starved “dead zones,” and contaminated drinking water. These blooms can release methane and nitrous oxide, making eutrophic waters significant greenhouse gas sources. By placing a value on each pound of phosphorus kept out of rivers and lakes, credits create a market incentive to adopt nutrient-smart practices. In effect, phosphorus credits are to water quality what carbon credits are to climate: they fund solutions that advance clean-water, biodiversity, and climate goals simultaneously.

Environmental agencies are increasingly using nutrient trading to meet clean-water mandates. For example, under the Chesapeake Bay cleanup plan, wastewater and industrial dischargers can buy phosphorus credits instead of building expensive in-plant controls if they pay farmers or landowners to adopt practices that cut runoff. Credits ensure that every pound of phosphorus avoided counts – helping regulators reach targets cost‑efficiently. Because phosphorus overflows degrade waterways and the climate (eutrophic waters emit >30% of global CO₂-equivalent fossil fuel emissions), these markets are critical tools for sustainable agriculture, water quality, and ecosystem health.

How Phosphorus Credits Work

Generating credits typically involves three main steps:

- Certification (Baseline Approval): A project is first reviewed to confirm it will generate real phosphorus reductions. This may involve site assessments or modeling to estimate how much P will be kept out of the watershed. (For instance, a farm might be certified to generate credits by installing cover crops or converting fields to forest, with predicted nutrient reductions.)

- Measurement & Verification: After implementation, an independent audit verifies that the promised phosphorus cut actually occurred (through monitoring data or models). Only then are credits issued. Many programs use standardized protocols (similar to the Reef Credit Scheme’s use of published methodologies, audits, and a public registry) to ensure credibility.

- Registration and Trading: Verified credits are recorded in a registry and can be sold to buyers that need offsets. For example, an urban developer facing a phosphorus permit limit can purchase credits from a nearby farm that reduced runoff. State programs typically list available credits (often by watershed) and track all trades to maintain transparency.

This “certify–measure–register” pipeline ensures environmental integrity. For instance, Pennsylvania’s Bay Cleanup trading program explicitly requires certification, verification, and registration before any nutrient credit can be sold. Eco‑markets schemes (like Australia’s Reef Credits) likewise use formal standards and third‑party audits to link on‑ground nutrient reduction to credits. Credynova’s platform can streamline these steps by integrating remote sensing, soil and water sensors, and blockchain-based registries to automate MRV (monitoring, reporting, verification) and speed credit issuance.

Project Types Generating Phosphorus Credits

A wide range of projects can generate phosphorus credits. Common examples include:

- Agricultural Runoff Reduction: Farms can earn credits by cutting phosphorus loss from fields and livestock operations. Practices include precision nutrient management (applying fertilizer only at needed rates/times), cover crops and no-till to hold soil and nutrients, riparian buffer strips, and improved manure storage or application. In Virginia, for example, landowners generate VSMP stormwater credits by permanently converting cropland to less nutrient‑intensive uses (e.g. restoring fields to forest, pasture, or hay). Such conversions provide long-term P reductions by eliminating fertilizer needs. Modeling tools or data estimates translate each practice into “pounds of P reduced,” which become credits.

- Wetland Restoration and Creation: Constructed or restored wetlands act as natural filters. As runoff flows through wetland soils and plants, much of the phosphorus settles out. Projects that create new wetlands or re-wet drained ones can thus generate credits. (Agencies quantify the increased nutrient retention using wetland models or empirical tables.) These projects also deliver co-benefits of wildlife habitat and flood control.

- Green Stormwater Infrastructure: In urban areas, building bioswales, rain gardens, permeable pavements and retention ponds catches stormwater and reduces the P load into streams. Cities like Washington, DC even have Stormwater Retention Credit markets where developers can buy credits from green infrastructure projects elsewhere. Virginia’s MS4 program explicitly lists stormwater BMPs and even shellfish aquaculture or algal harvesting as potential non-point credit sources. For instance, oyster farms on tidal creeks remove nutrients as oysters grow, and algal uptake can be captured by harvesting aquatic plants.

- Wastewater and Industrial Upgrades: Municipal and industrial water plants can generate credits by installing advanced phosphorus-removal technology that pushes their effluent below regulatory limits. When a plant reduces its discharge more than required, the excess reduction can be sold as credits under point-source trading programs. (This is effectively the inverse: point-sources generate credits to sell, while other sources buy them.) In the Chesapeake Bay program, for example, upgrades that achieve P removal below the permitted cap create tradable credits.

- Innovative Technologies: Emerging methods—like installing phosphorus-sorbing materials in drainage systems, recovering P as struvite from waste streams, or using biochar additives—could also be credited if proven to reduce net P loading. Each method would rely on an agreed-upon calculation (e.g. the weight of P retained in filters or products) to translate to credits.

By embracing these varied project types, nutrient markets tap into nature-based solutions and technological fixes alike. In all cases, robust MRV is key: projects must quantify pounds of P kept out of the watershed (often using a combination of field data and water-quality models) to generate the equivalent credits for sale.

Key Practices and Technologies for P Reduction

Successful phosphorus credit projects rely on proven best practices and technologies. In agriculture, regenerative and precision farming can make a big dent. For example, planting cover crops and reducing tillage improves soil health and cuts runoff, meaning fields need less phosphate fertilizer. Using manure more efficiently (or recovering P from it) also shrinks reliance on mined P. Indeed, experts note that changing farming methods (plus supporting a shift to regenerative agriculture) is crucial to lower nutrient pollution.

Engineered solutions complement field practices. Constructed wetlands and buffer strips physically trap and filter runoff nutrients. Green infrastructure like infiltration trenches, bio-retention cells, and rain gardens slow and clean stormwater. In wastewater treatment, tertiary treatment (e.g. chemical precipitation or advanced filtration) can remove the vast majority of phosphorus – often up to 80% or more. Emerging fixes include phosphorus capture systems (like struvite recovery reactors) and floating treatment wetlands planted with nutrient-absorbing vegetation. All these measures harness natural processes to lock up P.

Digital and monitoring technologies are also rising in importance. Soil and water sensors can track nutrient flows in near real-time, improving reporting accuracy. Remote sensing (e.g. satellite imagery) and GIS tools help model watershed conditions and verify that land-use changes (like reforestation) have the intended impact. These tech layers support transparent credit calculation and build trust in the market.

Case Studies: Phosphorus Credit Markets in Action

Chesapeake Bay (USA): The multi-state Chesapeake Bay cleanup effort includes well-established nutrient trading. Under the 2010 Bay TMDL, any new or expanded point source must offset its nutrient loads. Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania and others now allow regulated wastewater plants and developers to buy nitrogen and phosphorus credits to meet their limits. (For example, Virginia’s Bay Watershed Nutrient Credit Exchange lets wastewater plants sell extra reductions and lets municipalities or stormwater permittees purchase nonpoint-source credits.) Such trading has provided a cost-effective compliance path: Pennsylvania reports that its Bay trading program offers “a more cost-efficient way” for NPDES permittees to meet nutrient caps. Hundreds of credit projects (mostly agricultural land-use changes and stormwater retrofits) are now certified in the watershed, and trade volumes grow each year.

Great Barrier Reef (Australia): To protect reef health, Queensland developed the voluntary Reef Credits scheme. Landholders who implement approved practices that reduce nutrient and sediment runoff across the GBR catchment earn tradable Reef Credits. One Reef Credit represents a quantified unit of pollutant kept out of reef waters (currently defined as one kilogram of dissolved inorganic nitrogen, or 538 kg of sediment). Projects are verified by the independent Eco-Markets Australia. Buyers – including governments, banks, and corporations – purchase credits to support reef water quality goals. The Reef Credits program uses clear standards, accounting methods, auditing, and a public registry, illustrating how a credit market can be structured to deliver real water-quality improvements.

Baltic Sea Region: Europe’s Baltic Sea is threatened by nutrient overload under the EU Water Framework Directive and HELCOM action plans. Policymakers have explored nutrient offsetting and trading as flexible compliance tools. In fact, a 2021 study noted that while “nutrient trading systems for the Baltic Sea region have been proposed… they have not yet been implemented”. Pilot projects (such as experimental credit pilots for reducing agricultural P) have been discussed in Sweden and Finland. The coming years will likely see innovative trials or programs as Baltic states seek cost-effective ways to meet stringent phosphorus reduction targets.

Each of these cases shows the power of market-based solutions: by turning reductions into credits, governments and businesses can meet their water-quality or conservation obligations more flexibly. They also demonstrate the importance of standards and registries – from Virginia’s nutrient banking rules to Australia’s Reef Credits registry – to ensure every credit equals real, measured benefit.

The Market Landscape: Buyers, Sellers, and Platforms

Phosphorus credit markets are still maturing, but a few key players are emerging:

Buyers: These are typically entities needing compliance or seeking green offsets. Regulated buyers include municipal and industrial wastewater facilities, MS4 stormwater permittees, and developers facing state stormwater rules. For instance, small developments in Virginia can meet up to 100% of their P limit by buying credits. Beyond compliance, corporate sustainability programs, green banks, or even fisheries managers (for nutrient neutrality) could become buyers.

Sellers: Credit generators are usually farmers, ranchers, or landowners who implement nutrient-reducing practices. Conservation organizations and mitigation bankers can also develop large projects (like watershed-scale reforestation or wetlands). In some programs, even wastewater plants or stormwater utilities can generate credits by going beyond requirements. In Wisconsin’s new Watershed Trading Clearinghouse, for example, sellers are explicitly “landowners and agricultural producers” who adopt soil/water conservation practices, while buyers are “municipal wastewater/stormwater facilities and private industries”.

Platforms and Registries: Many programs use registries or exchanges to bring parties together. In the U.S., examples include RIBITS (US Army Corps registry for nutrient banks) and state-run registries. Virginia, for instance, maintains an online Nutrient Credit Registry listing approved non-point nutrient banks. Maryland’s Department of Agriculture and Environmental agencies have created a central registry and even a marketplace to catalog credits and trades. In Washington, DC, an online Stormwater Retention Credit Exchange lists available credits, prices and projects. Most recently, Wisconsin launched a Clearinghouse portal that “creates a centralized location for interested buyers and sellers” to match for phosphorus and sediment credits.

These platforms improve transparency: buyers can see who is offering credits (and for how much), and sellers can find interested buyers in their watershed. For example, in Virginia’s market, developers must purchase credits from the same watershed, and the state tracks credits sold on a public ledger. All told, the emerging landscape shows a mosaic of government, non-profit, and private marketplaces – from clearinghouses to brokerage platforms – connecting supply and demand.

Credynova’s Role: Enabling Nutrient Markets

At Credynova, we envision leveraging our MRV and marketplace technology to accelerate these nutrient-credit markets. By integrating satellite imagery, IoT sensors, and AI-driven modeling, Credynova can help project developers accurately quantify phosphorus reductions and document them. Our platform can automatically align projects with the relevant protocols (state or international), handle data reporting to auditors, and publish issued credits on a secure registry.

For buyers, Credynova’s platform can provide a one-stop marketplace listing available credits (similar to existing hubs) and offering due-diligence tools on each project’s environmental impact. Imagine a developer under a stormwater permit can log into Credynova, filter for phosphorus credits in their watershed, and compare options by cost and co-benefits. For sellers, we simplify the credit-generation process: our digital toolkit guides landowners through eligibility, tracks practice installation, and prepares verification reports.

This approach mirrors best practices seen in successful programs. For example, the Reef Credit program uses an independent registry and standard methodologies to ensure transparency; Credynova’s ledger can do the same for nutrient credits, ensuring once-and-only-once issuance. Meanwhile, lessons from clearinghouse models (like Wisconsin’s) show that tech-driven matchmaking removes friction. Credynova will further innovate by integrating nutrient markets with carbon and water credits, enabling “stacked” ecosystem finance for comprehensive sustainability.

Join the Nutrient-Neutral Future

The science is clear: we urgently need to cut global phosphorus pollution (UNEP calls for ~50% reduction by 2050) to protect water and climate. Phosphorus credit projects turn that necessity into opportunity. They reward land stewards for preventing pollution, help industries and communities meet environmental goals at lower cost, and deliver multiple benefits – from healthier soils and habitats to reduced greenhouse gases.

Credynova is eager to partner with farmers, landowners, developers, and ESG pioneers to make these markets thrive. Whether you own farmland or a watershed project site, we can help you turn your nutrient management into a revenue stream. If you represent a utility, company, or city aiming to meet water-quality targets or boost your nature-positive portfolio, Credynova can connect you with verified phosphorus credits.

Act now: join the movement to harness nature for water quality. Partner with Credynova and be at the forefront of pioneering phosphorus credit projects. Together, we can turn today’s pollutant problem into tomorrow’s profit for people and planet.

WhatsApp

WhatsApp  Book A Meeeting

Book A Meeeting